Union of Artists

There is something tragic, captivating, fragile, and enduring in those unions where both partners are artists. Such personal and professional partnerships fracture relationships into multiple facets: from successful co-creation to rivalry where in different periods one can observe plagiarism and triumph, betrayal, death, and immortality.

Without indulging in excessive romanticization, it is nevertheless true that when an artist chooses another artist as a life partner, both, in a certain sense, consent to a particular way of life deeply devoted to serving art, whether through its creation, destruction, or eventual oblivion. This condition appears especially relevant in countries with recently acquired independence and still-developing, often unstable cultural ecosystems.

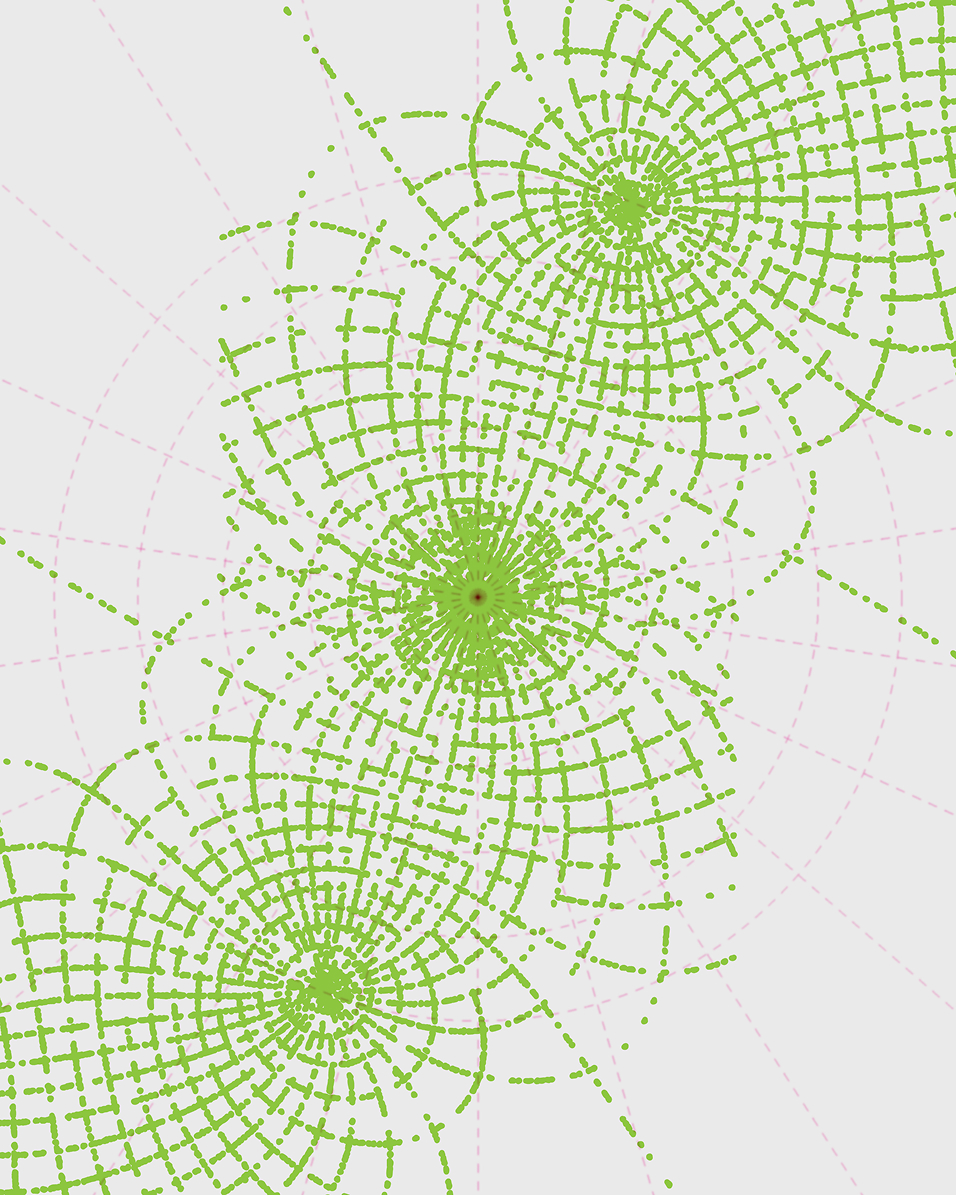

An infrastructure in which galleries, specialized education, museums, foundations, residencies, or art fairs are absent or nearly absent offers artists little sustained support or opportunity. In this context, artistic unions become, in a way, states within a state, small islands with shared values, accumulated knowledge and skills, and a self-sustaining system that regulates the distribution of responsibility and resources, growing from the ground up. This system is at once self-critical and grounded in unconditional acceptance; it is capable of existing for decades, enduring crises, shifts in political regimes, ideologies, and technologies.

The self-organization of artists as a means of preserving independence, while living in close partnership with another person equally committed to understanding life, is deeply compelling. Especially when one considers how tightly intertwined the sensual and the rational, the private and the public, the everyday and the emotional are within such unions. Much becomes shared: studio space, works in storage, bank accounts, and strong — often uncompromising — egos.

At the same time, the number of artistic duos in Kazakhstan, and in Central Asia more broadly, is so substantial that even a modest preliminary study undertaken in anticipation of this exhibition identified no fewer than twenty such partnerships, the majority of which are represented in the exhibition. These individuals have influenced and continue to influence not only each other’s artistic languages (a task that in itself seems considerable), but also share the lived experience of life. This creates additional pressure: for them, work does not end upon returning “home from work.” Within the domestic space, they continue to be colleagues, critics, censors, and professional partners to one another.

This observation gains particular sharpness in light of the recent opening in Almaty of two major cultural institutions: the Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture and the Almaty Museum of Arts. At this moment, significant for the country’s cultural history and, in many ways, triumphant for artists, there emerges a desire to look more closely at artistic unions and the works created within them, in order to delineate the space “before institutions.” To reflect on how art existed for many years outside large-scale cultural mechanisms, without support or validation — often marginal, resistant, and, in a sense, unprotected.

This exhibition is about a time that will forever remain in the past; about what happens to art before it enters history; about the artist’s journey from solitude to love, from the secluded to the institutional, from the experimental to the professional.

The exhibition is dedicated to Galim Madanov.